Ainay-le-Chateau, Summer, 1968

Documentary on the Town, and Film Diary of La Belle Au Bois Mourant, which name was subsequently changed so many times that no one can recall under which one it was issued, either in the French or English versions.

Producer: Maya Films, Henri Lange; Director: Jean-Pierre Bastide ("Boeuf"); Script Writer: Michel Martens; English version by Roy Lisker ("Pussycat", as in "What's New Pussycat?"); Principal Actors: Daniel Ghelin, Anouk Ferjac

I. Thursday, August 8, 1968

There are two villages called Ainay in this region of the Bourbonnais. Ainay le-Viel is 30 kilometers from here on the other side of the town of Herrison ( "hedgehog"). Off to the west lies theForêt de Tronçais, once ( like most of the national forests of France) a royal hunting domain.

In all respects we are au bout du monde- at the end of the world. Whatever its history, (and it appears that Ainay-le-Chateau was a fortress of some importance in the Middle Ages), it is now only a small out-of-the-way curiosity. Downhill from the square squats the remains of an old archway, one of those oddly impressive hunks of masonry that hang over an ancient European town like a battered helmet. High above the archway stands a round clockface, giving the archway its name: Tour de l'Horloge.

A southern branch of the Route Nationale does passes under the archway. It is otherwise isolated, far from the train lines and poorly serviced by local buses.

A southern branch of the Route Nationale does passes under the archway. It is otherwise isolated, far from the train lines and poorly serviced by local buses.

The main street seems little more than an enlarged mountain path, a single long winding thoroughfare, from which narrow, crooked medieval passageways branch off at on both sides. Surrounding the parking lot in the principal village square one finds a few cafes, restaurants and souvenir shops.

As I and the film crew entered the village this morning we commented on what appeared to be an abnormally large number of alcoholics. I counted at least a dozen myself, all in various stages of deterioration, sitting or standing in the doorways holding their little bottles of pinard on their laps, gyrating down the streets.

There were'nt many women. Most of the men were middle-aged, but no clochards in the Parisian sense. As a rule they wore the standard farmer's beret and blue cover-alls, with an occasional frayed jacket or work apron.

Later that day Henri, the Belgian technician, told us what he'd learned. A large portion of the population of Ainay consists of mental hospital inmates and out-patients. Those who aren't staying at the asylum

At night Ainay-le-Chateau is as silent as the tomb. Not a soul on the streets, no hum of traffic, nor the crackle of a radio. One comes face up against the night as to a solid wall, shut in by the narrow medieval streets, the squat houses, fragments of the old castle, moat and fortifications, the clumsy outlines of the clock tower.

Several of us went into the Café Industrial before dinner to get a drink. About two dozen men were huddled about the main counter gazing at the television set. Most of them looked as if they'd been pressed through a clothes-wringer: dreadfully worn faces, distended leers of suspicion, with much fatuous though inoffensive giggling. Impossible not to be repulsed, yet fascinating.

One of them came over to us with a green book and a Bic pen, wanting our autographs. He'd once been, or fancied himself a journalist; he would be haunting the film set all through the production.When we stepped out again into the street we encountered another group standing together in the parking lot. They wore the standard blue coveralls and had the same general aspect of mental cases. They'd been waiting for us. The presence of a film production in this isolated village had galvanized public attention. We would be the sensation of the region for months to come.

The men broke ranks and started walking quickly in our direction. Blanche Pigaud, the maquilleuse ( make-up artist) started to retreat but we assured her that they were perfectly harmless. Henri and I waved to them as we passed by; they waved back in return.

It was a classic game: they wanted to see how disconcerting they could be without frightening us away. In a way each group was on display for the benefit of the other. After we'd passed the square a few of them followed us a short way into the darkness before turning back.

This haggard band of tattered, unbalanced souls seemed the very image of the starry night: van Gogh would have been in his element. Behind them the dim glow of the Café Industrial; on every side the charcoal shrouds of impenetrable blackness. Au bout du monde in the fullest sense of the word! And, in this extinguished solitude, the pale green aura of madness. Returning to the village I saw a brick and timber yard to my right, in it a man hard at work, spitting in all directions.

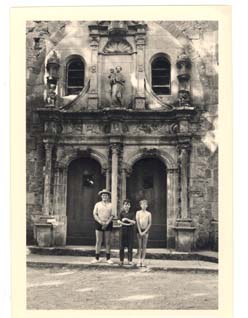

The church's facade is noble and simple and appears to be of ancient date. Its' two narrow doors remind one that in the Middle Ages human beings were shorter than they are today. Above the entranceway a Pieta, very ancient and the pride of the village, rests in a niche .

The church is built of brick and mortar. Here and there on its walls one comes some concrete patches, otherwise it shows few signs of major reconstruction. The sides are partly covered with moss, which joins with grass in covering the lower edges of the sloping rooves. Their unevenness, the way they have of molding over the stone walls like cardboard and clay, contributes it tone of quiet grandeur, evoking the metaphor of the soul's stumbling advance towards God.

Above the side entrance to the church at the left a plaster statuette of St. Francis beams in the lintel of the door. His right hand grasps a Bible, a begging bowl is in his left. In back of him is a scallop shelled vault, faded golden stars shining in a sky of pale porcelain blue. Framing its head is a great arch holding a ceramic sculpture of a tortured Christ. Affixed to a crucifix by rusted metal bands the body contorts in gruesome agony.

The church is built from 3 massive blocks. Low on the north side one finds the rotunda, surmounted by a tiled conical roof that looks like a hat. Next to it stands a grey rectangular brick block. Its window holds a panel of stained glass behind a grill. Surmounting it is a steeply inclined roof.

Finally there is the main body of the church. It holds many irregular protuberances jutting out at unusual angles. These are the niches for the private chapels, each with its own stained glass panel.

The composite gives one a strong impression of ascension, an impulse picked up and carried to completion by the powerful thrust of the spire and bell-tower, rising from the asymmetric arrangement of chapels like a mighty tree lifting up from underbrush. At the top of the bell tower there is, once again, an oddly shaped conical hat covered with asbestos shingling. Above this an unpretentious cross.

We now enter to examine its dim, peaceful interior. Rococo and 19th century styles predominate although several styles compete for one's attention: Gothic, baroque, romantic, abstract modern stand side by side.

The writing on the panels indicate that the stained glass was crafted by one Emile Thibeaud of Clermont-Ferand in 1860. Particularly captivating is the stained glass in the chapel of St. Solange. The artist has captured in the face of this saint a burning humanity. Her eyes are warm, unafraid, almost intimidating. Her face radiates spirituality. Even the folds of the garment that envelopes her are invested with life. In her left hand she holds an upraised quill. Beside her walks a greyhound, carrying an amphora dangling from a satin cord held between its teeth. The symbolism and the colors work as a unity. The warm deployment of gray in the panel communicates a spiritual quality of spiritual plainness or humility. In the face is concentrated the light pouring forth from this simplicity.

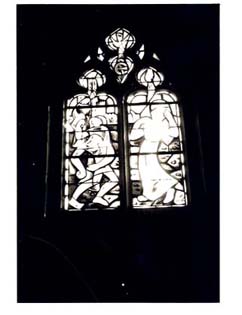

A modern panel depicts the martyrdom of St. Stephen.

The interior appears to have the shaped of a tunnel. Seen from the inside the roof does not appear to conform to the external gables of the church. At its north end it converges to a dome covered with tarnished murals. The surrounding chapel niches hold familiar objects: statues covered with gold leaf, altars covered with white cloths, prayer candles, flowers, presents of various kinds.

In front of the church one finds a small park holding 5 trees. The ground is covered with decaying leaves, even though the trees are in full bloom. The sun breaking through the over-hanging clouds gilds the church entrance with a spray of gold. This warm light falls on the barren, forbidding ground, dispersing the chill and stirring the topsoil of old memories. Sitting alone in this park one begins to meditate over all the things that may have taken place in the sad, romantic setting over the centuries, what love confessed, what silent grief dispelled, what ambitions conceived or repented, what clandestine pledges of faith, what scenes of departure as young men bid farewell to hurry off to the wars.

From every side descend the converging lines of a patchwork quilt of all the village's has ever been: the joyous crooked roads, the meandering walls, the smoke-filled huts, their bricked crests suggesting habitation in centuries past. One imagines the dawn, the daylight, the dusk, then the black night falling over these mulling settlements, the soap and laundry cauldrons boiling in the early morning, the yards full of chickens, the monks on their daily rounds, the peasant women in their gardens at the break of day.

And in the center of this ageless round of life stood the village church, giving its benediction to all this wearisome toil, much as its massive form resolves all the aimless, tortured meandering of the multiple lines of paths, walls and rooves converging around it.

Friday, August 9th:

After breakfast I made a short tour of the village. The local industries are brick-making, wood-cutting and small farming. Because the Route Nationale passes through it, there is a dribble of tourist trade. Any connection with modern France seems completely out of character. At the far end of town I came upon a field where workmen stood heaving sod, and cows lay about chewing cud. A rabbit hutch nearby . In some of the back yards I saw cabbage patches. Many of the cottages are new. Multi-colored plastic streamers were draped over the opened doorways. I was later told that these were the houses of the hospital personnel.

Saturday, August 11

The Church of AInay-le-Chateau

On the day after our arrival Henri Lange advised us to visit the "11th century church" in the lower part of the village. Getting there one turns left from the clock tower, down a spiraling passageway to the lower village. Here one finds a small square surrounded by a few shops. Directly in back of the square to the north one finds the church.

In a patch of dust and green, surrounded by low huts with sloping rooves shingled with red brick tiles stands a vision from the Middle Ages. To the right a decaying sandy wall follows the uneven contour of the road. Here in this virtual hermitage of lost souls stands this beautiful St. Stephen's church, its conception undimmed by time.

In a patch of dust and green, surrounded by low huts with sloping rooves shingled with red brick tiles stands a vision from the Middle Ages. To the right a decaying sandy wall follows the uneven contour of the road. Here in this virtual hermitage of lost souls stands this beautiful St. Stephen's church, its conception undimmed by time. Both style and content set it apart from everything else in the church. On it stand two brutes out of a canvas by Hieronymus Bosch, hurling with ferocity stones at the frail, helpless figure of St. Stephen. Behind this scene of violence rises the figure of an angel with sorrowful features. In the background the sketched outlines of a city.

Both style and content set it apart from everything else in the church. On it stand two brutes out of a canvas by Hieronymus Bosch, hurling with ferocity stones at the frail, helpless figure of St. Stephen. Behind this scene of violence rises the figure of an angel with sorrowful features. In the background the sketched outlines of a city.

Ainay, Town: Continued

Return to

Home Page