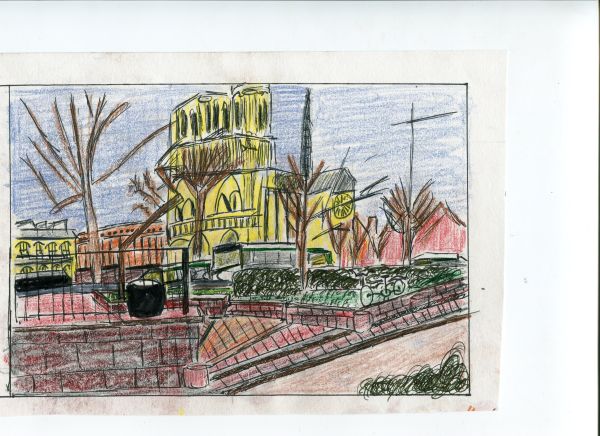

Notre Dame, as seen from the sidewalk outside Shakespeare and Company.

Drawn from a photograph, June 2012

Paris, February, 1968

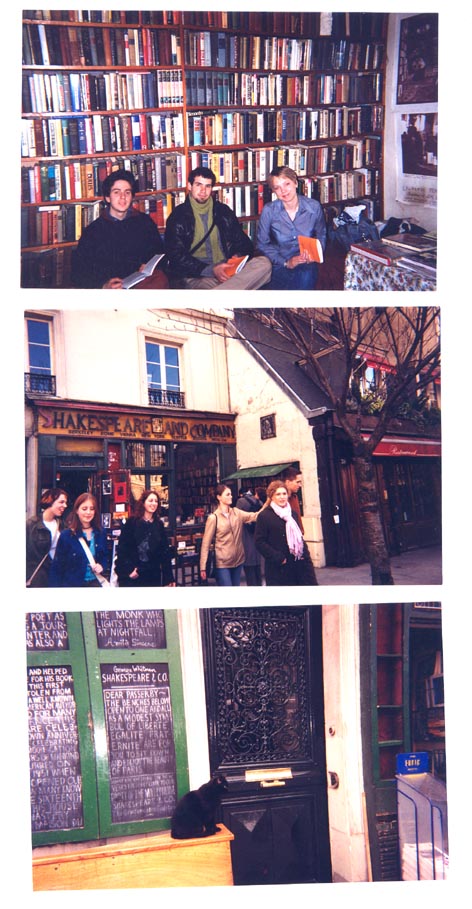

George Whitman's Shakespeare & Company

A week after my arrival in Paris George Whitman, the irascible, eccentric, dedicated founder and owner of the American bookstore, Shakespeare & Company invited me to stay in the "Visiting Writer's Guestroom" on the second floor of the store. It turned out to be nothing more than a broken-backed couch hidden away in a maelstrom of books and magazines.

Shakespeare & Co. is situated on a tiny street, la Rue de La Boucherie, at the foot of the rue St. Jacques, close by the Seine. It may lay claim to the best scenery in all Paris, an unobstructed view of Notre Dame cathedral. Historically these street names have sinister connotations. During the 100 Years War there was an uprising, known as the Jacquerie, centered on the rue St. Jacques. The rue de la Boucherie was the site of the Butcher's Guild, which ruled Paris for a brief spell with hammer, knife and ax.

It wasn't much in the way of lodging, but I had very little money and it was free. In addition Allen Ginsburg, Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Henry Miller had all used it - the couch that is - though for what purposes one could only surmise. George's infatuation for writers is beyond anything I've encountered, before or since. One might call him the Don Quixote of booksellers. Indeed he looks a bit as oneimagines the Knight of the Rueful Countenance might.

On the third night I made a swift and dramatic exit back to the hotel room I'd occupied the week before on the rue du Bac. My bags were quickly hauled out the front door and the key left on the front desk.

It took about a week for us to run into each other again. I was strolling down the rue de la Huchette, an old winding thoroughfare crammed with restaurants. From across the street a hoarse,rusty voice called out my name :

" Roy! Roy Lisker! Come on over here!" I turned around to confront George:

"I 'm sorry you weren't happy in the Visiting Writer's Guestroom."

" I'm afraid I wasn't. After I bought food for a week you sold the stove." One complaint, I thought, would serve for all the others:

" That's no problem. The stove's still there. You can still cook your stuff; it's all there in the refrigerator."

" Didn't the girl take the stove?"

" Well, she wanted the stove at first. Now she tells me I can keep the stove, but she wants the refrigerator! In fact that's why I'm here right now. I'm looking for someone to help me move the refrigerator onto the street."

I made the fatal, though inevitable mistake:

"I'll help you."

" Roy, I really appreciate that. Let's go. However, we ought to find someone who's strong. You're just like me: all skin and bones."

(These pictures were taken during a return visit to Paris in 2001)

Together we went into Le Petit Bar, a hangout for globetrotters, runaways and rich layabouts on the rue St. Jacques, to find Gregg. Gregg was from West Germany. To escape the draft, he'd fled to Paris, where he passed himself off as an American student from Cleveland. His English was a flawless mid-Western American's! He's picked it up hanging around American Army bases as a child.

Together we went into Le Petit Bar, a hangout for globetrotters, runaways and rich layabouts on the rue St. Jacques, to find Gregg. Gregg was from West Germany. To escape the draft, he'd fled to Paris, where he passed himself off as an American student from Cleveland. His English was a flawless mid-Western American's! He's picked it up hanging around American Army bases as a child.

He was where I expected to find him, at a table with one of his girlfriends. He asked us to wait until he'd finished off his beer. Then, with considerable reluctance he walked with us the half-block to Shakespeare & Company.

The bookstore comprised two oddly shaped floors, each of them divided into half a dozen rooms. When we got there George walked us up to the second floor. Coming to the refrigerator, he got down on all fours and proceeded to clean out 15 years of accumulated trash underneath it.

Standing before the opened door of the refrigerator was a pretty German girl. She was dipping a sponge into a pail of ice-cold water and using it to rub away food stains several inches thick. For some unaccountable reason both she and George were wearing dress clothing for this messy work. Her green woolen coat must certainly have been expensive.

By this time George had squeezed himself into a narrow 1-foot square section of exposed floor between refrigerator, wall, stove and sink. He was crouched down like a mouse digging for cheese, scraping madly at the base of the refrigerator with a butter knife. I was sent downstairs, with instructions to stand underneath the rotting driftwood staircase while George lowered one end of a wire through a hole in the floor. My job was to stand on a bench and grab the wire, then pull it through all the way.

Finally the wire came down and I pulled. This initiated a cannonade of curses from George. He yanked the wire back through the hole and advised me to 'watch him very carefully' as he now dropped the wire through the 'right hole', the one he'd meant to use in the first place. Sure enough a few minutes later the wire came slithering down over shelves of French paperbacks. The end of it was grasped and pulled through a book of poems by Blaise Cendrars. I jumped off the bench and allowed the wire to accumulate in a pile on a floor.

Almost immediately all the lights in the store went out. George was swearing a blue streak, accusing me of causing a short circuit by dropping the end of the wire in a puddle of water. This made absolutely no sense to me, given that the wire wasn't connected to anything; however there were as many loose and dangling electric wires in Shakespeare & Company as there are vines in a rain forest. Leading from nowhere to nowhere, with little or no insulation, many of them were joined together by little more than Scotch Tape or a band aid. Short circuits were daily occurrences

The problem that faced us now was moving the refrigerator down the stairs in near total darkness. George went downstairs and returned with some red candle stumps. When they were ignited the scene took on a funereal intensity. As George stood in the kitchen and shouted instructions to us, Gregg, I, and a hapless customer who'd just come in through the front door coaxed the refrigerator down the staircase and out towards the street. On the way the refrigerator's door-handle got hooked onto a bookshelf and wouldn't budge.

We told George that the door would have to come off. He wouldn't hear of it: "It's only the handle", he insisted " Not the whole door. Just lift it up over your heads to clear the bookshelves and carry it out the front door." But we held our ground and George had to relent. The door was removed and the refrigerator taken out to the street and left on the curb.

George gave Gregg and me some money for beers at Le Petit Bar. While we sat there Gregg filled me in on the details of his life as a fugitive. All of his documents were fraudulent or forged: passport, student cards and residence permits are hand-me-down gifts from friends: on each document he was a different person. He showed me an international driver's license. It was stolen by one of his girlfriends from her own father.

Gregg had to wander the streets of Paris night after night in search of a place to crash. He usually found a girlfriend, present or past, to put him up for the night. During the day he literally pissed away on beer the few francs he was able to earn, borrow or steal. By the time evening came around he never had the 10 francs sufficient for a cheap hotel room.

The previous night had been spent in Le Petit Bar, where people bought him drinks until 2 in the morning. Then it closed for a few hours, and he went across the street to an all-night cafe, returning to Le Petit Bar at 6 for breakfast. He left, came back again at 9, andcollapsed over a table in the back where the management allowed him to sleep until noon.

he rest of the day, before he'd met up with George and myself, had been passed under one of the bridges over the Seine, smoking pot with two girls, one French, the other Italian. The Italian girl had frightened him: he thought that she might be crazy and should be put into an asylum. I asked if I could meet them: of course, he said. They were so stoned when he'd left them that they were probably still there. But when we got there only the Italian girl was left.

Her name was Paula. She'd escaped 2 months before from an orphanage in Naples. Her hands were jammed into the pockets of a blue trench coat. Stiff black hair fell down over her eyes.

Paula spoke fluent French, very rapidly with a thick Italian accent. To us she babbled incoherent phrases, obviously high as a kite. There was nothing insane about her from what I could see. She was both intelligent and literate. In her pocket was a copy of James Joyce's "Gens de Dublin" . She'd also tried to read "Finnegan's Wake" in French but gave up. I told her that most native speakers of English have the same reaction. A few weeks later when I ran into her again on one of the bridges, she was reading D. H. Lawrence's "Plumed Serpent". I realized that she understood what she was reading when she began asking me questions about Mexico.

Over the next few months, as I came to know her better I also discovered that she may have been the most skillful street hustler in all Paris. Unlike Gregg she never had to worry about a place to stay. Her ingenuous,helpless orphan's charm, her intelligence and youth, were enough to get whatever help she needed, whether room, board or money, from just about any group of students or tourists. Sometimes she was sent back out on the street for petty theft; but even then she managed to find ways to get a good night's sleep. Some of her favorite places were the empty stone fountains around Notre Dame. They are kept heated and their interiors are invisible from the sidewalks.

Her biggest coup was the theft of a pair of policeman's boots, after she'd been arrested and taken to a police station during one of the student demonstrations of May, '68.

Return to Cities