Scotland 8/25/06-9/8/06

Episode 3

The Glasgow School of Art

Sunday, August 27,2006

Getting onto Renfrew Street from the Sauchiehall Mall requires that one mount a steep incline packed with dustworthy square cement paving blocks, reminiscent of San Francisco but with none of the Bay area charm. I couldn't imagine anyone attempting a pi/4 slope in the winter, or at any time when the sidewalks are coated with ice, sleet, fallen leaves or slime.

The taxi driver to whom I made these comments, in an attempt to reassure me, explained that winters in Glasgow are rarely severe. It is Edinburgh, buffeted by the winds from the North Sea, which gets the bad weather. Glasgow is warmed by the Gulf Stream, which makes an upturn on the western Scottish coastline. He claimed that there might be only half a dozen days in which ice coats the streets. Then the city's Department of Public Works sends its trucks out early in the morning to cover them with grout.

This may be the case, I told myself, but Chaos Theory requires that there will sometimes be savage winters filled with recurrent blizzards. It made me think a bit about the numbers of art students going to and from the Glasgow School of Art hospitalized for broken limbs. It was only the further reflection that, to the credit largely of the great Sydenham, Edinburgh Hospital had the reputation of being Europe's best medical school for 3 centuries, which alleviated my worries(both for the students and for the Cause of Art!)

2 views of the GSA from Renfrew Street

The splendid sandstone building facade of the Glasgow Art School makes a sheer level face with the cobblestones of narrow Renfrew Street. The school was designed by the acutely "touched" ( the ambiguities in this word ( "genius" or "madness ?") , renders its employment felicitous, to say the least) architect, painter and craftsman Charles Rennie Mackintosh, who in 1896, at the young age of 28, was handed the commission by the company that employed him.

Grants were doled out in dribs and drabs, with the result that there was a gap of about 8 years, 1899 to 1907, between the building of the two halves of the school. It was the Age of Decadence, of Loie Fuller, Gustav Klimt, Maeterlinck, Isadora Duncan, Edvard Munch and Richard Strauss - when Aubrey Beardsley sketched priapic revelries, Oscar Wilde lived them, Max Beerbohm was naughty and Wyndham Lewis beastly, when the Oxford intelligentsia thought it no longer proper to compare their mothers to Queen Victoria, and Bertie Russell was just about to build universe models on logic, and logic on sex. In such an era one could not imagine an eclectic artist at the level of a Rennie Mackintosh failing to take advantage of the multiple ironies present in the construction of a discontinuously jumped timeline art school!!

As revealed by our tour guide, a recent graduate of the school named Doug, the rooms, corridors and walls of the Glasgow School of Art abound in multiple reminders, metaphorical, symbolic, hieroglyphic and physical, of intersections of the two halves of the building, what one might call "rites of passage" at the boundaries of the transitions between them.

On the morning of August 27 I paid £5 to a receptionist in the small lobby near the entrance to the GSA, and joined a crowd of about 20 people waiting for the tour to begin. Doug showed up around around 10:30. I estimated his age at 25. He was thin but muscular. His red tee-shirt bore the silk-screened imprint of an image of a popular rock star ( I assume he was popular) . His black hair rode above his head in a thick bush, like an ocean wave painted by an Impressionist. His facial expression was not reassuring at first, as if he were sizing us up, but we soon discovered that he was simply shy. He spoke too quickly, with an accent I'd never encountered before. After awhile, when the shyness wore off, his monologue was very engaging. After being enrolled in the school for 4 years he was eager to let us in on its quirks. There was a woman in our group who came from Durham, his hometown in England. She offered to help me by translating what he saying . After a while this too was not longer necessary.

The tour

Charles Rennie Macintosh (1868-1928) was strong-willed, imaginative, his remarkable sense of humor stained by dark sinister streaks, mischievous and eccentric, though never without purpose. ( According to the Wikipedia, I'm eccentric. ) It was a unique time in European history when eccentricity was normal, and normalcy was considered eccentric, as opposed to our own times in which eccentricity is eccentric and normalcy is eccentric.

Charles Rennie Mackintosh

Yet above and beyond this Rennie Mackintosh was a mite strange; which is a way of saying that he got away with more than his fair share of eccentricity, without descending into outright lunacy- like Van Gogh without the ear missing- or Nietzsche without the horse - or Ezra Pound without the paranoia - or Gerard de Nerval's lobster without Gerard de Nerval.

Here is what Mackintosh himself has to say about the power of imagination:

" The artist may have a very rich psychic organization - an easy grasp and a clear eye for essentials - a great variety of aptitudes - but that which characterizes him above all else - and determines his vocation - is the exceptional development of the imaginative faculties - especially the imagination that creates - not only the imagination that represents. The power which the artist possesses of representing objects to himself pervades them - and their tendency towards symbolism - but the creative imagination is far more important. The artist cannot attain to mastery unless he is endowed in the highest degree with the faculty of invention. "

The art historians have no trouble assigning him a place in their chonicles: a mediator between the William Morris Arts-and-Crafts Movement and the rather vague movement dubbed Art Nouveau; heir to the Pre-Raphaelites and the Symbolists, participant in the Munich and Viennese Secessions (for which he designed several exhibition spaces). He figures as a precursor and in some sense a founder of the Bauhaus Movement, as can be seen from this quotation:

"Every object which you pass from your hand must carry an outspoken mask of individuality, beauty and most exact execution. From the outset your aim must be that every object which you produce is made for a certain purpose and place."

His affinity for Bauhaus can also be seen in his predilection for hermetic symbolism, and his endorsement of the speck, the line and the circle over more sinuous forms.

Traditional "decadence" manifests itself in extreme aberrations of taste, tending to preciousness, fastidiousness, unsavory affections and egocentric affectations without (if the artist is credible) migrating to the extremes of caricature or pathology , though he or she may on occasion go overboard. Max Nordau might call it "degeneration", which is the strongest stamp of approval one could imagine. However, if Charles Rennie Mackintosh was decadent he was not degenerate - in contrast to, for example, Wagner, who appears to have embodied both qualities in the same person.

All of this by way of introduction to Rennie Mackintosh's attitudes towards flowers.

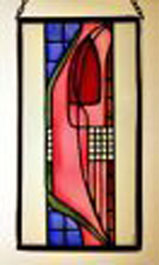

Mackintosh flowers

Ornamental pillars and niches are fashioned one both sides of the doors of each of the classrooms. In the past elongated glass vases were set into each niche - Mackintosh had a veritable passion for elongation, a hallmark of Art Nouveau. The school maintained an on site greenhouse on the top floor. From it the gardeners cut fresh roses each morning and deposited them into the vases. Charles Mackintosh's intention was that this should remind students to seek for the sources of their art in nature itself. Yet his actual practice seems to owe more to artifice than to nature, more to Oscar Wilde's creed of "Nature imitates Art" than the reverse. Dramatically emphasizing the perpetual clash between Nature and the Idea, the glass panels inset on the upper portions of the doors themselves depict highly stylized roses, more in the manner of boutonnieres , all with exceedingly elongated stems.

Charles Rennie Mackintosh's predilection for black comedy, (sometimes spiteful though, restrained by taste and wit from being altogether malicious) , resonates through the building. As we strolled through the corridors on the second floor, Doug directed our attention upwards to a row skylights. They evoke images of oversized lampshades or clothes hampers. Doug described them a mix between traditional Japanese decorative motifs and fanciful Irish harps. Mackintosh collected Japanese art all through his career and was strongly influenced by it.

We continued on through the corridors and the 3 floors.Doug made us aware of some of the things that Mackintosh did to literally "turn the building upside down". Mackintosh had been a student at the earlier Glasgow Art School, and one can surmise that he must have been storing up ideas all the while about what he would do to it if he ever got the chance! The phase "turning the building upside down" refers to a consistent program whereby features that one associates with basements appear on the top floors, and rooms in the basement are designed like those normally built on upper stores. Bouleversé, one might say, and vice versa, a la Versailles! When we ascended to the top floor we encountered a succession of alcoves, stairwells and open spaces that had the gloom and dankness of a basement dungeon. Yet immediately afterwards we would walk onto a landing cast in dazzling sunlight.

Staircase to 3rd floor

To reach the top floor we gyrated along a narrow staircase. The outer and inner walls of this staircase are shielded by painted black metal fencing, artful arrangements of metal bars and grates, a kind of prison phantasmagoria. Throughout this construction Mackintosh has introduced hieroglyphic shapes bespeaking some kind of private symbolic language as if one were entering the shrine of some ancient Druidic cult.

Mackintosh took these tokens very seriously. It appears that when the board of trustees looked at his drawings they were interpreted as scratches, or mistakes, or otherwise superfluous. On the first round the builders neglected to include them. When Mackintosh discovered this he flew into a rage. The entire cage was ripped out and replaced by one conforming to his original specifications!

The Center and East wings of the Glasgow School of Art were built between 1897 and 1899. Construction of the West Wing went on from 1907 to 1909. The two sections of the building are demarcated on the inside by a pungently black line in vertical descent along their juncture. The materials and technologies involved in their construction are also different and reflect the great advances in the employment of steel and concrete in construction at the turn of the century, associated primarily with Glasgow and Chicago, the two industrial powerhouses of that time. The similarities in the ideas and careers of Charles Rennie Mackintosh and Frank Lloyd Wright are more than coincidental.

Boardroom. window and ceiling lamp fixture

The first building had windows looking out from all sides. When the second half was constructed many of these were blocked by stairwells, reducing the amount of natural light for illuminating the studios. The mammoth windows in the original building caught the sunlight streaming in from every direction. When the west wing was added many of these windows were blocked off. After making a tour of the first floor Doug brought us into the Board Room on the second. Half of its windows are blocked off by a staircase that was added later. In spite of this unfortunate situation, the Board Room is a miracle of light, imagination and intelligent design. The remaining windows, tall and somewhat concave, admit a sparkling illumination from the street enlivened by the play of shadows created by networks of vertical and horizontal slats .

It was consonant with Mackintosh's philosophy as an architect that he concern himself with every aspect of a building, down to the furniture, decorations, tapestries, rugs and so on. All of the chairs in the Board Room had been designed and constructed by him. Too frail and too valuable to be used today, they were lined up in a row against the walls. After we'd filed in we sat in ordinary bridge chairs around a simple folding table of the sort one might pick up in a department store. Merely sitting in such a room and regarding one's surroundings is a sheer delight.

This opinion was not shared by the board members and trustees in the 1890's. The financiers and industrial tycoons who ran the enterprises in the "Scotch Chicago" had a vested interest in harvesting a crop of graphic artists for the purposes of industrial design, advertising and construction, and it was from this aspect that they had viewed the goals of the school when they'd agreed to serve on the board. Their uneasiness, and indeed disapproval, of the Board Room as a place in which to hold their meetings, were summed up in the comment that it looked "too feminine" ! Obliging as ever, Rennie Mackintosh, though a decadent Symbolist painter, exemplar of all the " horror of the feminine" present in their imaginations, built a new Board Room for them on the first floor, dark, heavy and ugly. This appeared to have suited their tastes perfectly, and seems to have been a typical Mackintosh prank, which means that they had no idea they were being satirized. The original Board Room was restored to its original function in the 60's and has been in use ever since.

Along the left wall are displayed photographs of the close friends and collaborators of Rennie Mackintosh. After himself comes that of his wife, also an artist, Margaret McDonald, of whom he said, quite sincerely: "I have talent, she has genius ."

Margaret MacDonald Mackintosh

Herbert McNair, another painter and close friend, married Margaret's sister Frances. Pictures of both of them hang in the photo gallery. The connections of Mackintosh, McNair and the two sisters went back to their years together as students at the former Glasgow School of Art. One is charmed to read that they youthfully called themselves "The Immortals" (a name subsequently changed to, simply, "The Four". When they exhibited together in Europe they received the further label of "The Spook School") , and produced a magazine called, simply, "The Magazine", in which Mackintosh consciously imitated the style of Aubrey Beardsley.

Alonside them is a picture of Francis Newbery, director of both the old and new Glasgow School of Art, in the creation of which he was the driving force.

Kate Cranston

Finally there is a photo of Kate Cranston, manager of a string of tea rooms designed by Mackintosh. She, too, was an eccentric, of the crow variety. The photograph in the Board Room shows her wearing a broad flowing skirt with thick furbelows from an earlier part of the century. She had no use for the industrial boom or much else associated with the modern world, and was more than a little autocratic. We learned this from a visit to another room, set aside as a museum for the furniture and other crafted items created by Mackintosh over the course of his career.

Mackintosh chair;

presumably for some high dignitary

Mackintosh did not just make a chair: each one was closely tailored to the person, the status of that person, and its intended function. For example, the chairs designed for the board members have backs of different heights, each reflecting the hierarchic standing of the person expected to use it. The back of the "chairman's chair" is ridiculously high! Once again, the irony seemed to have been lost on the worthies using them. Looking at these cleverly designed chairs, one imagines them as stage props for a film like "The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari".

Kate Cranston's chair

For the instauration of the grande-dame Kate Cranston in her Willow Tea Rooms, Mackintosh built a chair with an exceedingly wide settle and base, allowing her robes to cascade like Niagara Falls over its length down to the floor. The high semi-elliptical back is broken up with regular bands of holes, like a fence or Japanese screen. By turning the chair away from the restaurant she could shut herself off in a private space, inaccessible to the clientele. Turning it back she could once again hold court.

On the same pedestal, standing alongside Kate Cranston's throne are several versions of a chair Mackintosh designed for the use of waitresses employed in the Willow Tea Rooms.Their intended purpose was that they were be occupied during the rest breaks of 20 minutes or so to which the waitresses were legally entitled.

Their backs are very low, less than a foot, and would eat into the spine of anyone of normal height. Cross-latticed rungs on the legs of these chairs make it impossible to find a position for resting one's legs or feet, while the seat is inclined in such a way as to encourage the body to tip forward. Underlying this novel construction was the intention that the waitresses would be so uncomfortable that they would automatically jump off these chairs before their twenty minutes were up and go back to serving customers! Once again it is difficult to say whether, in designing either the throne or the stools, Mackintosh was only carrying out instructions from Kate Cranston or if he was laughing at her, probably a combination of both.

Other evidences of the ironic twist to Mackintosh's somewhat sinister mind are built into the architecture of the school itself. Upon reaching the 3rd floor we were led into a fragmentary section of a crypt, low interlacing arches that put one in mind of a medieval monastery. It is here where, in the past, students would have to sit while awaiting test results, interviews with teachers or appointments with the administration. If we were to believe Doug ( and one must allow some scope to his imagination as a recent graduate of the school), their having to sit there would frighten them into a proper attitude of respect for authority!

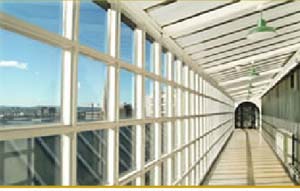

Adjacent to this niche one enters a long gallery very much in the exhilarating style of the Board Room, flooded with sunlight from the row of glass panes running its entire length on the left side. Through them one is presented with a magnificent panoramic view of the northern cityscape of Glasgow. In Mackintosh's day the city was still largely undeveloped in this direction and, apart from the streets and buildings one saw landscapes, meadows, hills and farmland. Up to the present students sit at this skylight and draw, with the slats defining the individual panes serving as picture frames.

3d floor gallery

The greenhouse was situated further along and to the left of the gallery. It was there that students planted and cultivated flowers to take home with them and continue their training in drawing from nature.

On the right side of the gallery, behind the containing wall are a number of rooms that, in the past, were for the exclusive use of woman students and were nick-named "hen rooms". Making a lame attempt at apology, Doug claimed that the word "hen" used to describe a woman in Scotland is intended as a compliment, but I was skeptical, particularly in the light of what he'd told us about the objections of the trustees to Mackintosh's first Board Room.. After all, why were the women segregated in the first place? (We know why, of course: it would not have been seemly for girls of good family to be drawing the naked bodies of male models. )

Our final destination was the library. Art historians have described it as "the masterpiece within the masterpiece". To me it looked like a cross between the gingerbread house in "Hansel and Gretel" and the rooms of a cloister set aside for producing illuminated manuscripts!

The Library

Glasgow School of Art

Whatever its aesthetic merits it is far and away the most extraordinary room in the entire building. Walls, furnishing and partitions are all painted a somber black. Powerful sunlight streams through high windows like those in the Board Room. Diffusing through cross-hatched slats, light and shadow fall onto the desks and chairs, making sinuous patterns which Mackintosh himself likened to the vines and foliage of a forest interlaced in multiple layers of braids and knots.

Windows, Light, Space:

Library, Glasgow School of Art

The natural element is also stressed in the very straight "trunks" of the black wooden pillars, which he called "trees". Decorations on and around the legs and backs of the chairs and tables are carved in flaming shapes ( not unlike the arches in the Koh-i-noor restaurant) .

But nothing prepares one for the most amazing set of artifacts in this mysterious haven for the studious; the lampshades. These, hanging from the high ceiling on long black chains, are replicas in miniature of the skyscrapers that were being raised in New York and Chicago at the time the school was built! Macintosh's explanation of this metaphor was that the library ought to be dedicated to the fusion of Nature with Technology, the bounding themes of modern art.

Skyscraper lampshades

Glasgow School of Art library